It’s taken me nearly 2 years to write again, and even now I’m so uncertain about how I want to approach this piece.

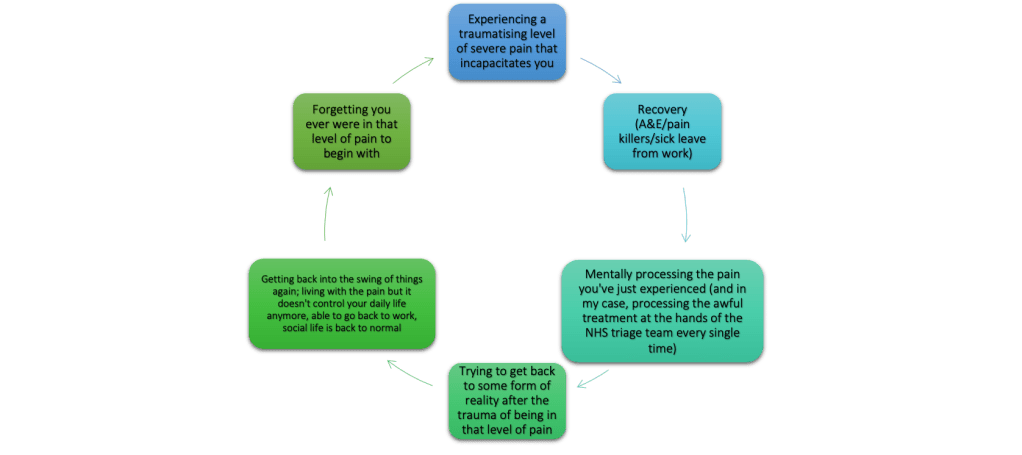

My last post was disheartening to read. The inevitability of the endometriosis coming back with a vengeance was hard to accept, and my future looked so uncertain. At this point, I can honestly say that my future has never been more uncertain. Unfortunately, with the severity of my endometriosis coming back, so have the hospital admissions. In the last two months alone, I was hospitalised three times, two of which required admission onto a gynaecology ward in two different hospitals. I never thought my condition could get as bad as it was before I was diagnosed in 2020, but as luck would have it, I’m in the worst position I have ever been in with this disease, and this is truly the worst pain I’ve ever felt in my life. 3 months of consistent pain, 10/10 in its severity, has taken its toll.

I’m so incredibly lucky to be under the care of an incredible endometriosis clinic at a hospital in London, and I want to start by saying that before anything else. Because it was an NHS referral, it took 5 months to get an appointment but when the initial appointment came through, the consultant took an extensive history of my condition, and did an immediate TVS (trans-vaginal ultrasound). I’ve had so many scans over the last 12 years that I wasn’t phased by another one, and was actually glad they were so quick with doing one in the appointment. In the TVS, they found an endometrioma on my right ovary (a cyst filled with menstrual blood that’s a common sign of endometriosis, also referred to as a “chocolate cyst”), along with some deep penetrating endometriosis, as well as adhesions around my bowel caused by the endometriosis. They also found that my right ovary was tethered to both my pelvic wall, and the side of my uterus, essentially meaning that my entire right side of my womb is stuck together. There was also a hemorrhagic (functioning) cyst found on my left ovary, but out of everything that came up on my scan, ironically that was the least concerning. I knew the endometriosis had come back so this wasn’t exactly surprising to me. It didn’t make it any less painful to hear, however. The only option after 2 laparoscopies not tried in managing my endometriosis was progesterone, the word I’d been dreading. Progesterone treatment had been recommended to me before, but I’m so hyper-sensitive to hormone therapy, and also have the Mirena coil, so the idea of more hormone therapy was terrifying. I’d previously looked into the side effects of progesterone treatment and it wasn’t pleasant. I’ve tried hormone therapy before that didn’t involve progesterone: before my first endometriosis surgery in 2020, I was tried on the Zoladex injection but had to give up after a month because of my mental health deteriorating to an all time low (https://anisahhamid.com/2021/02/05/my-zoladex-experience/). However, I was getting desperate at this point and was willing to try anything since I knew my situation was getting worse.

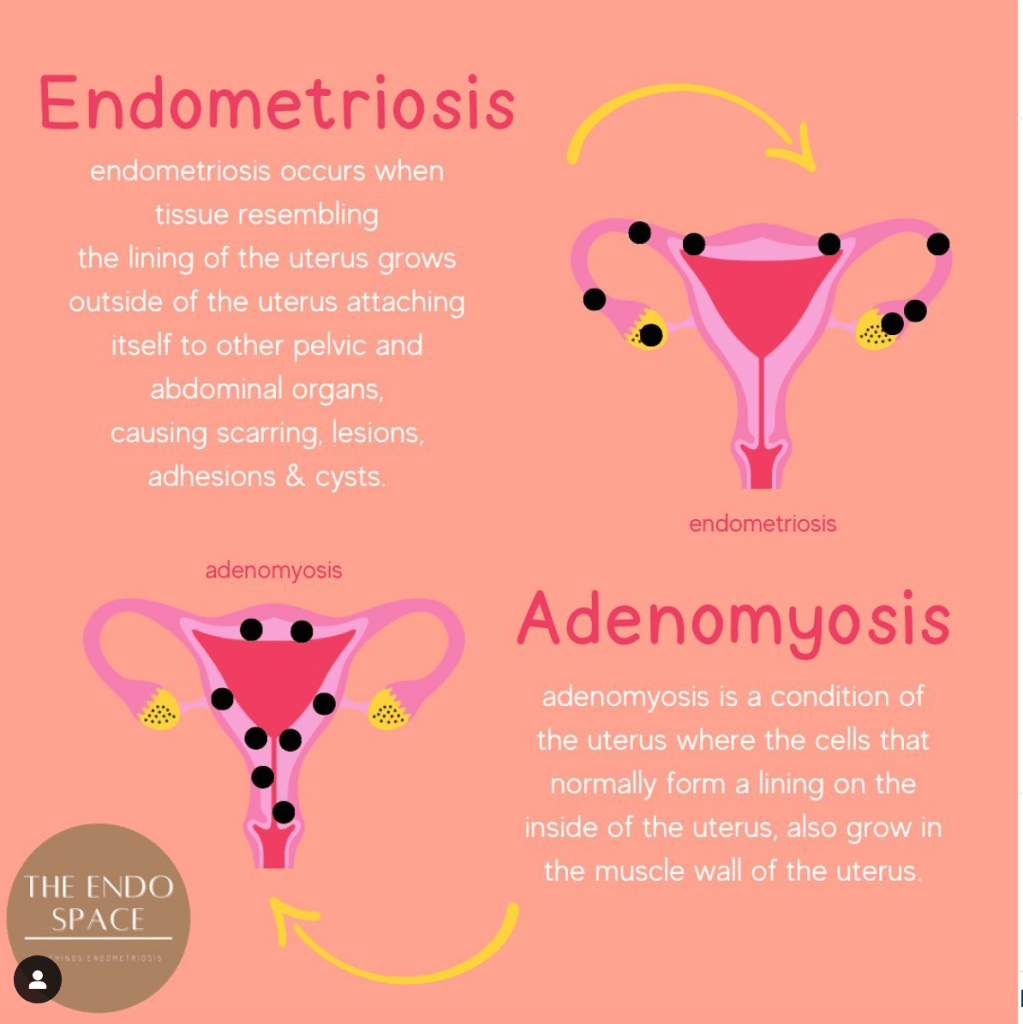

Unfortunately, the specific progesterone treatment I was put on didn’t work at all. In fact, I ended up in hospital three times whilst on the treatment, so it was clear that it wasn’t working for me. During one of the hospitalisations, I was incredibly lucky that the lead consultant of the clinic I am currently undergoing treatment with was working on-call in the gynaecology department that night, so she did another TVS to examine if the endometriosis had spread further, and to also rule out any ruptured cysts. They instead found I also had adenomyosis, which is slightly different to endometriosis.

Source: https://www.instagram.com/the__endo__space/p/CntVNOnPowf/

Following my third hospital admission, I was put on a different progesterone pill called Provera, with the initial dosage of 30mg (3 tablets a day). The on-call gynaecologist who came to see me the morning after I was admitted onto the ward described the Provera tablet as essentially tricking my body into thinking I am pregnant, which in turn should limit the growth/spread of endometriosis in my body and prevent any future flare-ups of pain. My main concern was the mental health consequences, of which another gynaecologist thankfully was very honest with me, and told me to come off the progesterone straight away if my mental health deteriorated to the point of being unbearable. I’ve always been adamant that I never want to compromise my mental health for my physical health. It’s a compromise that should never have to be made by women anyway when it comes to their health, and my mental health is just as important to look after as my physical health. Unfortunately, I was so desperate for a treatment to work that I did eventually end up sacrificing my mental wellbeing whilst being on the progesterone treatment. The side effects were brutal – morning sickness, fever symptoms, hot flushes which drenched my entire body in sweat, fatigue, brain fog, memory issues just to name a few. I also for the first time in my life, really experienced depression whilst my body was getting used to the progesterone. I know that this was a side effect of the pill but having been lucky in life to never have suffered from depression, my brain went into a state of shock. I truly hit rock bottom, and had never felt so low in my life. I didn’t think I could survive the feeling of being so down, without hope for the future and miserable at my prospects. Being in constant agonising pain all day everyday definitely exacerbated the feelings of depression, so it was a vicious cycle. I felt like I was drowning and I’d never come up for air again.

Thankfully, my GP realised I was suffering with the progesterone, and she decided to reduce my dosage to 20mg to help ease some of the side effects. I noticed an almost immediate difference in myself afterwards, and I’m so grateful that she listened to my concerns because that situation was truly untenable. Because my mental health was deteriorating so rapidly, my GP also made a decision I would normally have fought against: she put me on a low dose of anti-depressant. Initially, I was adamant that I didn’t want to be on a medication that would control my moods, emotions and feelings. I was scared that the anti-depressant would control me. However, the emotional turmoil of being in pain all the time, and being in the worst pain of my life, meant that I was struggling on all fronts and I needed a bit of help sorting through those emotions. I’ve found that it’s so easy to fall into a spiral of thinking “why is this happening to me?”, “what have I done to deserve this pain?”, “how much longer can I cope with this condition?” and “why have I been so unlucky with my health for so long?” Those thoughts eventually consume you until you creep closer and closer into the darkness, and the one tablet of anti-depressant has honestly helped me through those spirals. Now, I have a clearer head when it comes to my attitude towards my endometriosis and I don’t fall into the depths of those dark spirals. Don’t get me wrong, I’m still so far from myself and who I was – my mental health is at an all time low, and there are days when I can barely bring myself to get out of bed and face the morning. I’m struggling with the reality of my endometriosis coming back and being worse than it ever has been, and some days I don’t want to talk to anyone, even my parents. But the anti-depressant helps push me out of these moments, and I suppose stop them from getting any worse, which I am grateful for. The first two weeks of starting the anti-depressant however were the worst two weeks of my life – your brain essentially suffers a chemical imbalance and my moods were truly all over the place. It took two weeks for my body and brain to get used to the pill, and it was horrifically tough to get through. But, I knew it would be worth it for the end result.

Managing severe pain with painkillers has been a struggle of its own. For at least the last 4 years, if not more, I’ve been told to take anti-inflammatory drugs before I take any stronger opioid pain killers due to the potential for addiction, of which I am well aware. This extends to taking ibuprofen, and then later mefenamic acid (4 doses a day), diclofenac (3 doses a day) and most recently, naproxen (2 doses a day). What health professionals don’t tell you is that long term use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) will affect your stomach. Around the time that I started the Provera progesterone treatment, I noticed that I was having severe upper abdominal pain as soon as I ate food, almost within seconds of my first couple of bites of food. I was told it could be indigestion or dyspepsia, a side effect of progesterone treatment. I was prescribed some omeprazole which works to block acid in the stomach to help with the pain. Unfortunately, the pain only got worse and worse, to the point where I would be doubled over in agony after each meal, writhing around. The upper abdominal pain became worse than my pelvic pain, which is when I became concerned. I was referred for an endoscopy to investigate if there was anything going on in my stomach, to find that I’d actually had a stomach ulcer this whole time, as well as something called erosive gastritis. My stomach lining was eroding away and a hole was being burnt into it because of the NSAIDs I was on. It’s really hard not to feel completely let down by the healthcare system when something that could have been so easily avoided happens, as well as it being another condition I have to deal with on top of a disease that I’m fighting for my life to live with. It seems like people in healthcare are so concerned about prescribing stronger pain killers to manage acute pain, that they’d rather risk a 28 year old getting a stomach ulcer, despite the fact that I’ve shown myself to be the most sensible when it comes to my pain management. Thankfully, I am on medication for the stomach ulcer and feel so much better after starting it, so fingers crossed it resolves itself soon.

Being dealt blow after blow takes its toll when living with an incurable disease. The reality of my situation has been tough to accept, and I’ve spent so many years pretending, putting on a brave face and smiling through agonising turmoil. The reality is, endometriosis is a horrific condition. People very rarely take it seriously unless they’re specialists within the field, they don’t believe the pain you’re in, and they treat it like period pain. 5 organs in my pelvis had to be operated on to remove diseased tissue, and people still struggle to believe me. It’s even harder coming to terms with the knowledge that I’ve exhausted every avenue of treatment available now, at the cost of my mental wellbeing. I can’t stay on the Provera treatment for more than a couple of months, as the risks are severe and higher than other treatments. Which leaves the inevitability of surgery, which would make this my third laparoscopy to treat endometriosis. It’s overwhelming, and it’s incredibly sad. It’s exhausting. I’m exhausted, I’ve been fighting my body for so long, that I really am running out of fight. I have a follow up appointment next week, of which most of it is going to be spent telling the consultant about how awful my life has been over the last 3 months.

The hidden torment of this disease isn’t just physical – it’s psychological too. We’re fighting our bodies every day, every night, and then putting ourselves back together again so we can show up for our family, our friends, our workplace. I so desperately wish I could say that it gets better, but right now I really am in the worst situation of my life. I just hope to God that the next time I write on here, it’s more positive. Because the reality of endometriosis fucking sucks.

A x